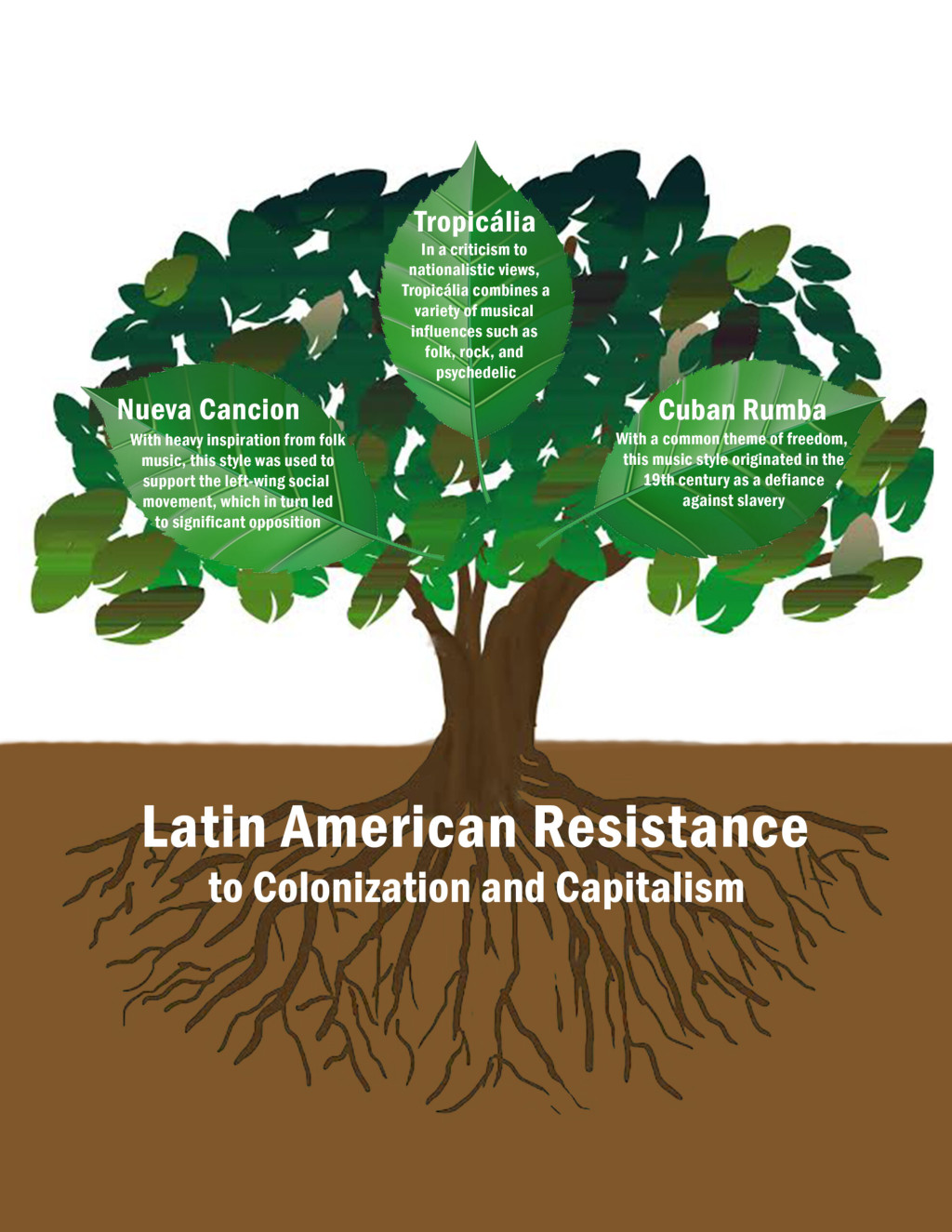

Latin America’s vibrant history includes stories of horrific oppression, then powerful resistance. Thus, many and varied musical styles have developed over time as a form of cultural defiance. Three particular styles created in resistance are Cuban rumba, nueva canción of Chile and Argentina, and Tropicália from Brazil. These genres have gone on to influence modern music in significant ways.

Slavery, and the ensuing transculturation between Spanish and African music, is something that had a great influence on rumba’s development. Early rumba, played in slave barracks, was an expression of the outlawed African culture — song, dance, and drumming all coming together. Interestingly, one can map some of the percussion used when rumba became a distinct genre of music to household items, such as frying pans translating to what became the catá, at least in their use.

As time passed, and more musical influences cropped up, rumba began to develop into what is referred to as “urban rumba,” which consisted of the styles of yambú and guaguancó. These forms, as the name suggests, developed more in the north of Cuba, in the urban areas of Havana and Matanzas. Here, rumba also picked up elements from the music of the coros de clave (street choirs who performed music using European instruments and harmonies), finally creating the urban rumba styles that are still in practice today.

One note regarding the influences of rumba is that it was of importance to the evolution of the son-based music, which was then adapted by jazz musicians. Exploring rumba as a genre will not only illustrate the strength and beauty of Cuban culture and history but will also grow your understanding of contemporary music genres which borrowed from the more traditional Cuban style. A nice place to begin with listening might be older recordings of the group Los Papines. They present good music, as well as an enjoyable performance.

Nueva canción simultaneously originated during the mid-1950s in Chile, Argentina, Cuba, and Spain, illustrating the cultural exchange happening between areas colonized by Spain. Musically, it was primarily a revival of varied traditional Latin American musical styles. Songs almost always feature guitar, and often folk instruments such as the cajón (drum) or the zampoña (similar to a pan flute). Lyrically, however, the music focused very much on social issues and followed similar trends to progressive social movements. As one can imagine, this angered the right-wing military dictatorships that swept through Latin America. Musicians performing this genre faced extreme forms of suppression such as censorship, torture, exile, or even death.

Artists of significance in nueva canción include Chilean Violeta Parra and Mercedes Sosa from Argentina.

Violeta Parra was one of the foundational artists in the development of nueva canción. This was thanks to her efforts to preserve Chilean culture and traditions, including proverbs and recipes, in addition to songs. The Chilean style of nueva canción can be traced in large part to cueca, a guitar-based Chilean song form. Nueva canción later unexpectedly exploded in popularity — in large part because of the 1970 presidential campaign of Salvador Allende, in which artists played a significant role.

Mercedes Sosa was also hugely significant to the motion of nueva canción and to much of Latin America as a whole. Having been forced into exile by the 1976 to 1983 military dictatorship, she brought nuevo cancionero — the Argentinian variant of nueva canción — to a global audience, performing in London, Brazil, Colombia, Canada, and Israel, as well as continuing to record albums throughout that time. She was also particularly well known for performing Violeta Parra’s “Gracias a la Vida,” a song that would become famous worldwide in no small part due to Sosa's performances.

Tropicália, or Tropicalismo, was a Brazilian artistic movement in the 1960s that ended in 1968, after many of its members were exiled from Brazil. Incorporating primarily music, but also film, theater, and poetry, it was predominantly driven by the principle of antropofagia (cultural “cannibalism”), or the idea of creating something new and original through different existing influences.

It faced political opposition from both the left- and right-wing groups of Brazil. Speaking out against the authoritarian Brazilian military government (also known as United States of Brazil or Fifth Brazilian Republic) earned hate from the right, and influence from Western capitalist popular culture garnered protest from Marxist-influenced students — who were strongly nationalistic in terms of their cultural and aesthetic intake — on the left. At the end of 1968, two of the leading members of Tropicalismo, Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, were arrested and imprisoned for two months, after which they were forced to go into exile in London.

If one is interested in Tropicália, a great beginning point is to listen to its manifesto, Tropicália: ou Panis et Circencis. A collaborative work by many Tropicalistas, spearheaded by Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, it was an original and unusual album mixing traditional elements with modern pop and rock, particularly British psychedelia such as the Beatles.

Rumba, nueva canción, and Tropicália have continued to have an influence, musically, socially, and politically. Songs from nueva canción and Tropicália are still covered by modern artists, and "Gracias a la Vida" lives on in the hearts and minds of many the world over. Of course, rumba is very much alive as both a dance and musical form. All these forms of music have strengthened and lifted up those who have listened to it, giving hope to fight for what is right.