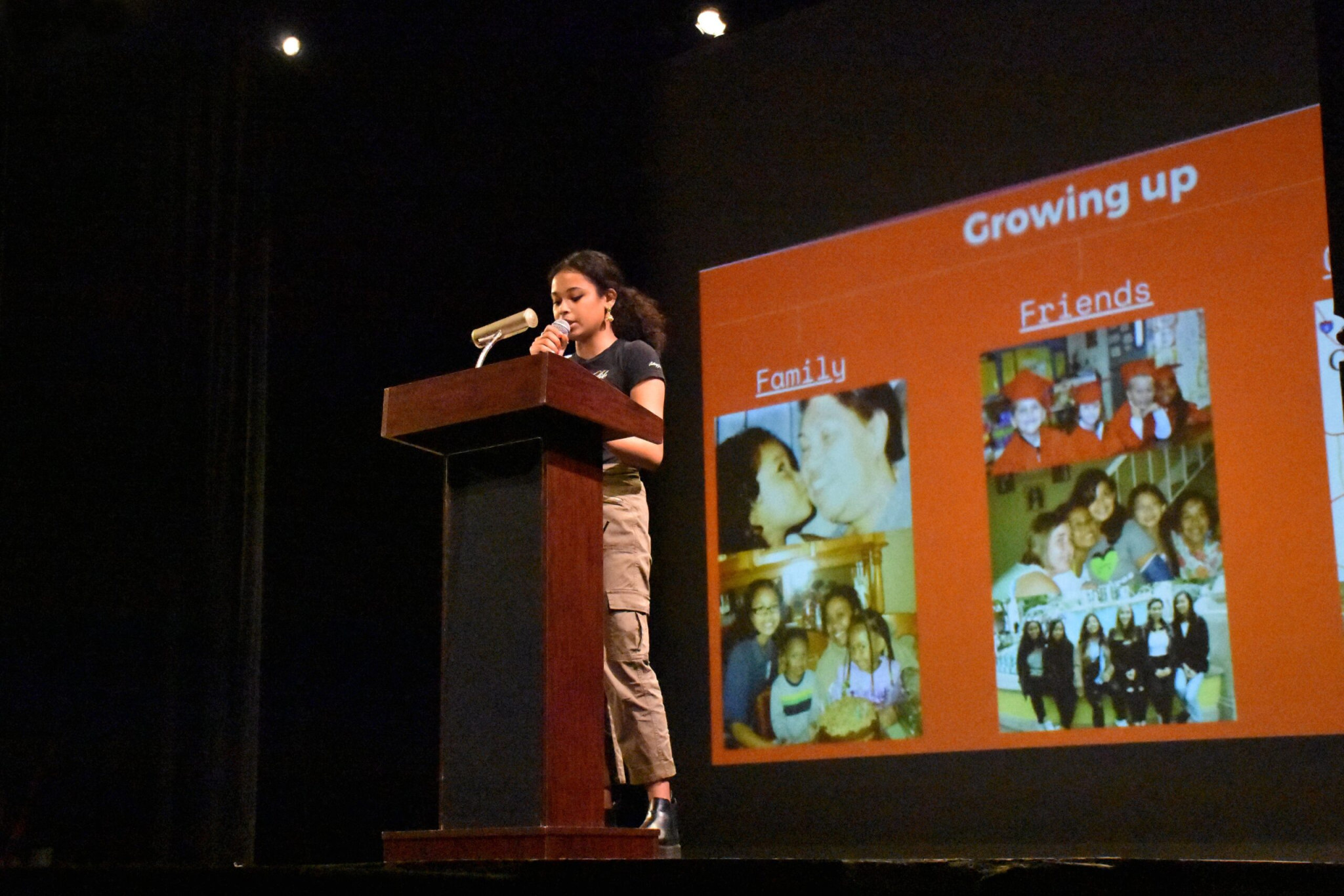

On Tuesday, March 3, Berkeley High School’s (BHS) Multicultural Student Association (MCSA) held its first speaker series. The event featured ten mixed speakers who spoke about their experience being of multiple ethnicities or races in today’s climate. The event was organized by BHS junior Gabriella Lerman, senior Jillian Curran, and senior Salaah Deen, the co-presidents of the MCSA.

The speaker series aimed to amplify the stories of underrepresented communities as well as provide a safe space for mixed students to come together. “We want to unite the diverse community here at BHS by giving individuals that come from marginalized communities the platform to share some very personal experiences,” said Lerman. The MCSA hopes that the series will help people feel more validated as they face our rapidly evolving society.

The mission of the series extends beyond building community and giving voice to the silenced — a large part of it serves to educate and inform. “It’s important for students who aren’t people of color or from marginalized communities to understand experiences that may be very different from their own,” said Lerman.

The first speaker of the event was Katrina Bullock, a University of California, Berkeley, student. Bullock, who is Black and Filipina, told her story of grappling with both sides of her identity. “I was constantly code-switching; I was never completely my authentic self. Everyone in my life only saw a piece of me, and even I never understood myself fully,” said Bullock. This was because she felt boxed in to act a certain way around different people. With her Filipino side of the family, she worried about sticking out as “too Black.” However, there was the opposite pressure with the black side of her family.

This was exacerbated by yet another standard to conform to — that of society. “While my Filipino relatives assured me that they saw me as first Asian then black, first Mulan then Princess Tiana, I knew that this was not so for the rest of society,” said Bullock.

Throughout her school years in Santa Clarita, where less than 7 percent of the population is black, Bullock was always seen as the “token black girl.” Whenever discussions of Martin Luther King Jr. came up in class, she was subject to awkward glances. Her classmates often assumed that she was an expert on all things black culture, ignoring her Filipina side. When walking with her Filipina mother, she would even be mistaken for someone else’s daughter.

Bullock never felt comfortable talking about Black culture with her Filipino friends or discussing Filipino culture with her Black friends. At all times, Bullock felt like she was only half of her full identity — the half that other people felt comfortable seeing.

The two sides seemed distinctly separate, and her parents never quite understood her experience of struggling to piece them together. While they both tried hard to empathize with the identity conflict that their daughter was going through, neither were mixed race themselves. They did not have the personal experience necessary to fully see through Bullock’s eyes.

Although it is still difficult to understand all aspects of her own identity, Bullock has grown a lot since her high school years. “Everyday, I am learning to be content with being confused,” said Bullock. “I’ve learned to decolonize my own mind. I’ve learned to see the commonalities instead of the differences between the two cultures,” Bullock continued.

Bullock’s presentation was followed by a panel of mixed BHS students and teachers.

A common experience for the panel of students and teachers was that of having only one side of their identity acknowledged by society.

Jack Egawa, a BHS senior, said: “Being half Japanese, most of the time people think I’m the most Japanese person they’ve ever met. They ask me things like ‘have you seen this anime?’ or ‘do you eat sushi every night?’ all the time. No!”

Another common thread was the difficulty of reconciling two historically conflicting identities. Amanda Moreno, a Mexican and white teacher at BHS, said, “My mother’s family are the same people who burned down homes and took land from my father’s Mexican ancestors.”

Egawa, who had a similar story as Moreno, saw something very valuable in his background. On his Japanese side, Egawa’s grandfather was sent to an internment camp during World War II, and his grandmother lived in Hiroshima during the same period. However, he identifies equally with his American side, who had been the perpetrators of anti-Japanese acts during the war.

By understanding the dueling cultures, Egawa was able to act as a bridge between them. “It gives me a unique perspective to be both a part of the dominant culture and still understand the other. I learned to become a mediator,” said Egawa.

Lerman explained her personal reasons for organizing the club and the speaker series: “My personal desire came out of struggling to figure out what it meant to be Latina in addition to being Jewish.” It can be difficult for mixed students to find each other because oftentimes, despite some shared experiences, they are all from different cultural backgrounds.

It can be difficult for mixed students to find each other because oftentimes, despite some shared experiences, they are all from different cultural backgrounds.For this reason, Lerman wanted to build a coalition of different minorities in hopes that unity would give them a much stronger voice. “I longed to find people similar to me and create a community for students who felt like a singular ethnic or religious club didn’t fully embrace and acknowledge the intersections of their identity,” said Lerman.

Through numerous meetings and other events, such as the speaker series and potlucks throughout the year, the MCSA continues to work towards creating a campus where no minority is silenced, isolated, or marginalized due to their background. This will hopefully create more understanding of the various cultures at BHS.

The MCSA envisions a world where collaboration and empathy between different groups will lead to a culture of acceptance and tolerance.