During the past year, everyone has had to navigate the ups and downs of the pandemic. However, it is women in particular who have taken a hit, both worldwide and in Berkeley. As women make up many of Berkeley’s caregivers and essential workers, they have been affected especially acutely by COVID-19.

Berkeley High School (BHS) English teacher Melissa Jimenez is a mother of two. Childcare, a duty that is more often than not assigned to women, has taken a particularly large toll on mothers during the pandemic, explained Jimenez. “The reality is that women are still often picking up the slack with the kids regardless of how progressive the family structure is,” she said.

Jimenez has put her eldest child, who is four years old, in a preschool cohort, while her one-year-old is taken care of by Jimenez’s in-laws while she teaches during the day. Though she is at home full time due to distance learning, Jimenez, like many other working parents, has had to find a balance between working and caring for her children. “I have a much shorter window of time to actually do my job during the day, and then a lot of my job has to get pushed to after my kids go to bed,” she said.

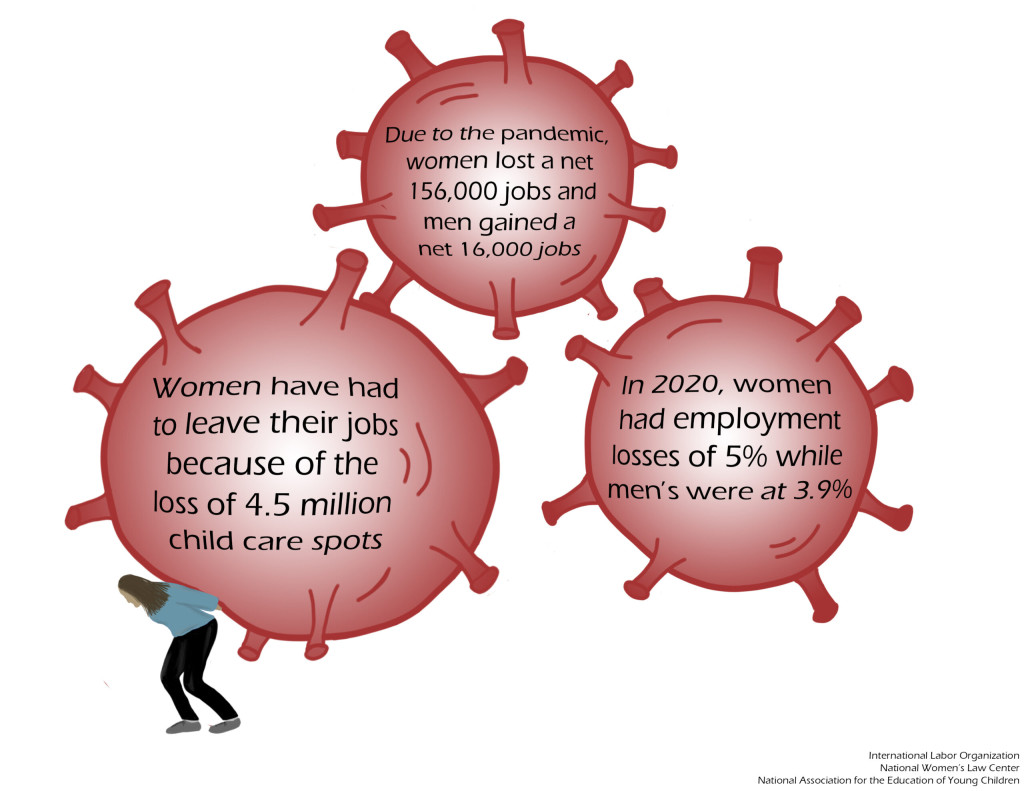

As a teacher, Jimenez has seen many of her female colleagues pushed to take a leave of absence during the school year in order to provide more support for their children. “You hear on the news all the time about the numbers, and the amount of women that have left the workforce because they had to make a choice,” said Jimenez, referencing how many women are having to quit their jobs in order to care for their children.

According to data from the US Department of Labor, 2.5 million women have left the workforce since the beginning of the pandemic, compared to 1.8 million men. Out of all American women, Black and Latinx women have particularly been impacted by job loss.

Jimenez said, “What I have seen [with] some of my colleagues at BHS who do have children, and women in particular, is [that] a lot of women were actually forced to take a leave of absence this year because they … didn’t want to put their kids in childcare and risk exposing family members.” She explained that many of the choices women are forced to make for their families often result in a downfall, whether that be a fiscal impact, or a reduction in the amount of time they have to spend with their children or in their occupation. This kind of choice, stated Jimenez, more often than not, falls on women.

Female small business owners have also taken a heavy hit. Namgyel Newton is one of the founders of Yaza, a women-owned clothing store on Solano Avenue that has been open for the majority of the pandemic. As a clothing and retail store that relies on customer interaction, Yaza had to shut down at the beginning of the pandemic. The business was only able to reopen five months later when a younger employee began working alongside Newton.

Newton said that like many female business owners, her experience during the pandemic has been a shift to a new sense of normal. She has had to reduce her expectations in general, from store sales to how activities during this time are limited. “That’s how I’ve survived during the pandemic,” she said.

Newton has a 12-year-old son at Martin Luther King Middle School. As a mother during the pandemic, she has had to dedicate more time to caring for her children without as many options for childcare, all while juggling the business she owns and keeping it alive. “It’s been challenging for a lot of women during the pandemic who also have to manage their kids,” she added.

Jacqueline Divenyi has been a Berkeley-based piano teacher for the past few decades, and the pandemic is the first time she has ever had to give online classes to her students. As many of her students attend Berkeley schools, her entire way of life has had to shift to a new sense of reality. “My house is always empty,” said Divenyi. “This is very hard because... I had all of these students coming and going and it was very alive.” Like many private music teachers, Divenyi is now alone after years of having students come to her house regularly for lessons. She continued to say that while many of her students are still able to take online classes, she has missed seeing students in person. “There is never opening the door to see a nice kid in front of my door. I feel much more isolated,” explained Divenyi.

While her own kids are grown up, Divenyi knows of women who have taken a hit due to lack of childcare during the pandemic. “Women who have children in school who have to stay home, and they also have a job, now that’s hard for them,” she said. She later referred to a woman she knows who has two young kids, and has had to put them in childcare while she works her day job.

Jimenez has been faced with a similar dilemma, having two young kids who crave human interaction. Jimenez and her family had to make a joint decision on what risks they were willing to take for childcare once the school year started. “I live in a multigenerational family, and … my kids’ grandparents interact with my children all the time. So you run that risk if you have a child in school or in childcare, that they could expose COVID to another family member,” she said.

Mothers’ guilt is real, explained Jimenez. What a lot of women are facing right now is the choice between their career and their kids, which has made a huge impact on mothers. Jimenez said,“If you’re doing your job … I feel like I’m making a selfish choice when really I’m going to enhance my students’ learning. But … because society conditions us to feel like our work is primarily first with the children, that if you take on any other purpose or meaning in life beyond that, which most working women do … it can take a toll.”