As we emerge from the soul-sucking year that was 2020, hope has surfaced in the form of a quick jab in the arm with a needle. Though California is still deep in the COVID-19 pandemic and faces some of the toughest months ahead, there is now an end in sight. The much anticipated coronavirus vaccines, produced by Moderna and Pfizer, are beginning to be administered. However, the question of what that process will look like remains unclear. Public sentiment towards the vaccines is also a concern, as widespread immunity depends on enough of the population being able and willing to be vaccinated.

There are two main issues at play with the vaccines. The first is a scientific one, while the second is a human issue.

For many, the most pressing concern that comes to mind is about the vaccine’s efficacy. Does the vaccine work? According to Professor Britt Glaunsinger, a virologist in the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology at University of California (UC) Berkeley, “The data and all of the scientific studies that have been conducted so far strongly argue that it is both efficacious and safe.” In fact, these vaccines have been shown to be significantly more effective than the flu vaccine.

However, an efficacious vaccine does not necessarily mean an effective response to COVID-19. A question that remains unanswered is exactly how far the vaccine will go in preventing transmission and eliminating or minimizing severity of infection. Professor Glaunsinger explained, “In order to halt the virus completely, you need a vaccine that is not only going to protect people from the disease but from getting infected at all.”

If the vaccine only prevents people from displaying or experiencing coronavirus symptoms despite carrying the virus, this would mean that even vaccinated people could still spread COVID-19. If this turns out to be the case, it would necessitate the wearing of masks and social distancing even between vaccinated people in order to prevent community spread. Until researchers completely understand the extent of the protections that the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines offer, people will have to remain vigilant, with life still unable to return to full normalcy.

This is where the human question comes in. Will people be willing to continue practicing social distancing and abiding by COVID-19 restrictions even after they have been vaccinated?

Zephyr Wells, a Berkeley High School (BHS) junior in Academic Choice (AC), said he will. “I’m already used to wearing a mask. If wearing one when I don’t need to lets us go outside, then I’m fine with it,” said Wells.

Even as people become immune, the government may need to continue to impose lockdowns and stay-at-home orders if people begin to become too relaxed about safety after getting a vaccine, potentially endangering others who are not yet immune. From what has been observed of human behavior so far during this pandemic, with millions of Americans refusing to wear a mask despite witnessing their friends and family contract or even pass away from the virus, ensuring responsible protections against infection is likely to be a continued challenge in the country.

However, before post-vaccination restrictions can be contemplated, there is the question of whether people will even be willing to take the COVID-19 vaccine in the first place. Professor Glaunsinger said, “A lot of people don’t want to get vaccinated. They are suspicious of the vaccine…. Many people are hesitant to be jumping in and taking it.”

Some of this suspicion is a result of politicization of the vaccine by the national government, while some of it is uncertainty towards the very new vaccine and its potential and still unknown side effects. Claire Renoe, a BHS alumni from the class of 2020, shared, “I wouldn’t want to take it now because the side effects are still unclear.” Renoe went on to say that she would take the vaccine, however, “once there’s some more research on it.”

Hopefully, as more people get vaccinated — especially public figures and officials — many will begin to feel increasingly comfortable with the vaccine. Prominent figures on both sides of the political aisle, such as President Elect Joe Biden and Vice President Elect Kamala Harris, as well as Vice President Mike Pence and Senator Mitch McConnell, have all gotten vaccinated live in front of the press in past weeks and more figures are planning to do so in the future.

Like Renoe, Auvie Deriada, a junior at BHS, is wary of the side effects. Deriada said, “I wouldn’t take it now if it was offered because I still don’t know the side effects.” So far, these mentioned side effects have appeared to be temporary and not a true danger to one’s health.

Vijay Bhandari, a doctor at the Contra Costa Regional Medical Center who received the coronavirus vaccine on December 29, 2020, reported experiencing a few side effects. “I got a wave of fatigue and muscle aches — kind of like you’d have with a bad virus. Like a flu kind of thing, but nothing beyond that. If I had to work when these symptoms kicked in, I could have,” said Dr. Bhandari. “Everyone I’ve talked to has experienced pretty much the same thing. And those symptoms lasted less than 24 hours.”

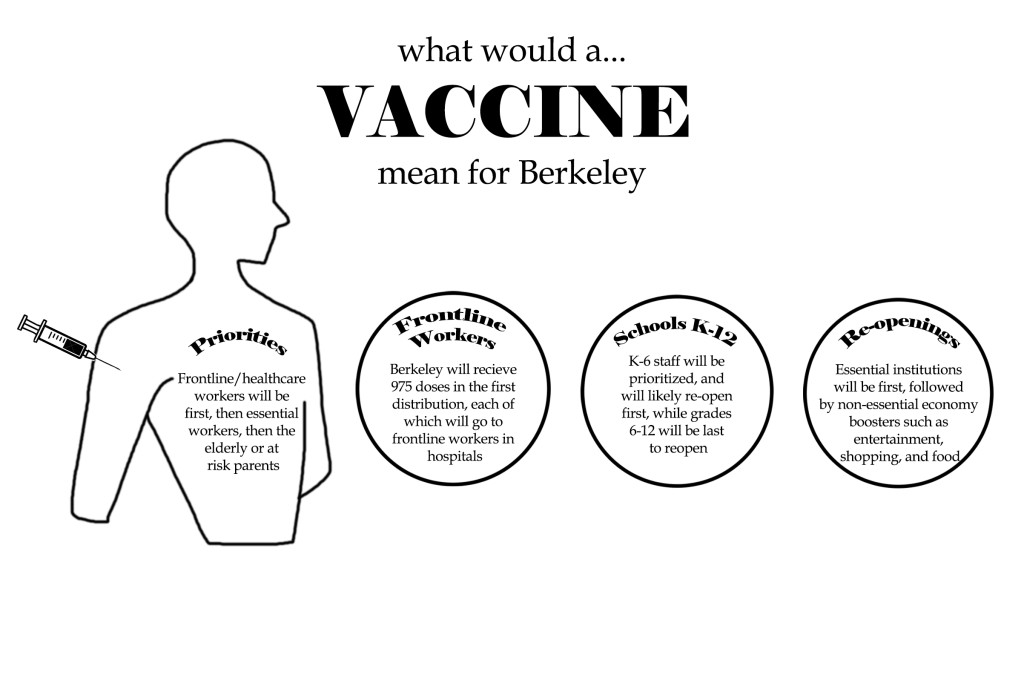

Vaccinations in Berkeley have already begun, with healthcare workers at Berkeley’s Alta Bates Medical Center having received their first doses of the Pfizer vaccine in the last weeks of 2020. According to Mayor Jesse Arreguin, the City of Berkeley had received precisely 975 doses of the vaccine by the end of December. The State of California has received under 1.3 million doses. As each individual requires 2 doses of the vaccine, these doses were only enough for around 1.6% of California’s population of roughly 40 million people. However, more are on the way in 2021, with Joe Biden promising at least 100 million doses of the vaccine administered in his first 100 days in office. The state of California expects to have enough doses and supplies to vaccinate most Californians by summer of this year, which begins June 20, 2021.

Because of the current scarcity of vaccines, there is a vaccination triage of sorts. California has several tiers that define when different people will be receiving the vaccine. The first tier includes healthcare workers, nursing home residents, and people with more than one significant medical condition. Tier two includes those with one significant medical condition, people over 65, prisoners, homeless people, and teachers. Tier three includes young adults, children, and essential workers. These tiers are then followed by the general population.

According to the New York Times’ tool to track one’s place in the vaccine line, if California were made up of 100 people, the average Berkeley High School student (around 16 years old, with no pre-existing health conditions) would stand around 50th in line to receive the vaccine. That being said, both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines have not yet been approved for those under 16 years old, so younger BHS students may have to wait longer.

Are students patient enough to wait for their turn in line, giving priority to others? Sasha Wizelman, a junior at BHS, said, “I’m pretty patient.… Because I’m not old or immunocompromised, I’ll probably get it sometime [this] summer.” Gili Stein, another junior, agreed that it was important for others at higher risk to receive the vaccine first. As for getting vaccinated himself, Stein said, “I’ll get it when I get it; I can wait.”

Some question why it is so important for healthcare workers to get vaccinated before those with severe medical issues. Dr. Bhandari, who works directly with COVID-19 patients, explained, “We’ve definitely seen where the hospital’s capacity to take care of really sick patients is heavily impacted by small outbreaks…. All of a sudden, a group of nurses or doctors or therapists … can’t go to work anymore because either they got infected or have to quarantine.” If healthcare workers are unable to work, patients who are hospitalized will be unable to receive the care they need, thus leading to higher mortality rates.

As a healthcare worker working closely with coronavirus patients, Dr. Bhandari was in the very front of the vaccination line and received his vaccine just recently. “I was definitely excited about it, because there’s always [a worry] in the back of your head that you could become sick and then bring the virus home to the people that you love,” Dr. Bhandari recalled.

Melanie Thomas, a psychiatrist at the Women’s Health Center at San Francisco General Hospital, received a vaccine on December 31, 2020. Dr. Thomas, who is married to Dr. Bhandari, said she felt differently about receiving the vaccine than her husband. “For me, it was a mix of emotions. Mostly excited, but also a sense of privilege and sort of wishing in a way that I could give my vaccine to my mom,” Dr. Thomas explained.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought grief and isolation to millions and blatantly exposed inequities in American society, but the arrival of the vaccine provides hope that things will begin to improve as the months go on.

However, this optimism will only become reality if everyone does their part. COVID-19’s disappearance is dependent on people’s trust in science, as well as their ability to follow the advice that research has laid out. Stay home, wear a mask, and get vaccinated when the time comes.

Update: This article was changed to include correct names and gender pronouns.