“I don’t know how to describe how angry I was when we got the call that [Matthew Bissell] was no longer hired here and the story had not gone public,” said Berkeley High School (BHS) yearbook teacher Genevieve Mage. “That meant that he was about to scuttle off into the dark, move to another school district, and no one would know. I was about to lose my goddamn mind.”

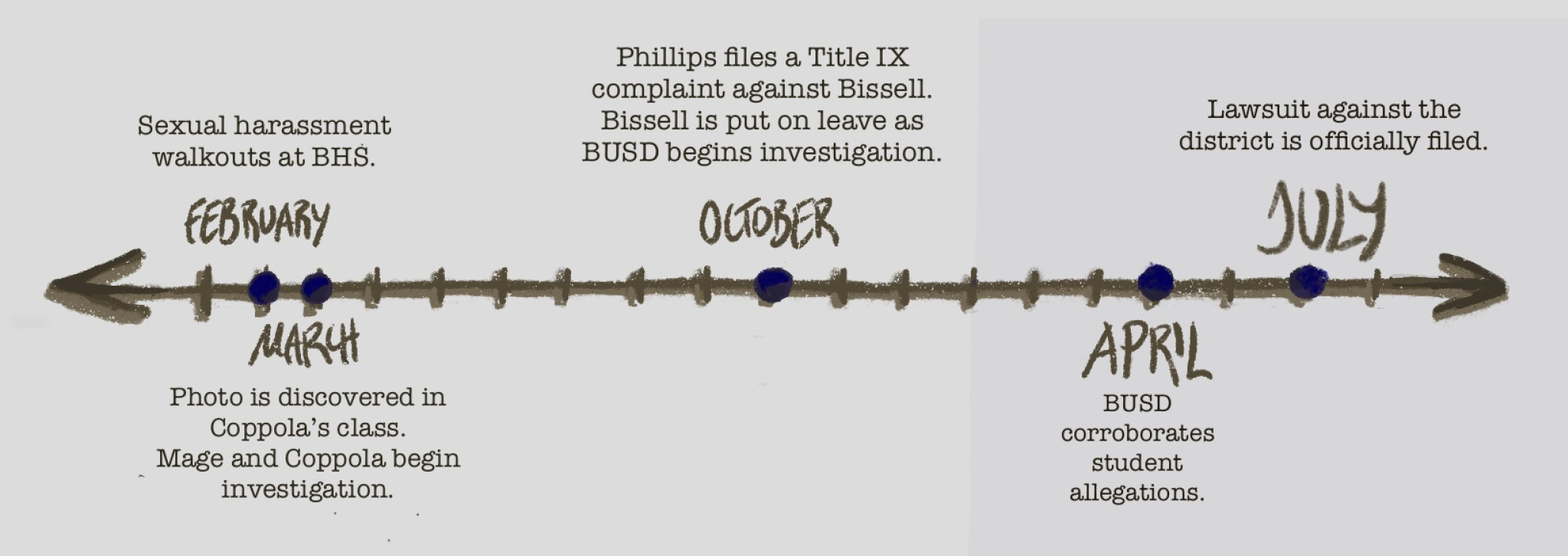

A week after receiving that call, BHS alum Rachel Phillips called Mage to tell her that she had found a lawyer and was planning to file a lawsuit against Bissell and the Berkeley Unified School District (BUSD). In April, a district Title IX investigation corroborated claims that Bissell sexually harassed and assaulted several current and former BHS students, including Phillips back in 2003.

The lawsuit, filed in June, claims not only that Bissell sexually harassed Phillips and other students, but that the district failed to protect them after repeated complaints to school officials. One significant piece of evidence is a 2003 yearbook photo showing Bissell hugging Phillips from behind, with a caption labelling Phillips as “most likely to date a teacher.”

Academic Choice (AC) teacher Angela Coppola discovered this photo just weeks after the BHS sexual harm walkouts in early 2020 demanded more protection for students and survivors. After showing it to Mage, they, along with BHS Stop Harassing Parent Advisor Rebecca Levenson, began the search for students who had filed similar complaints against Bissell.

Doing “everything the district asked me to do,” Mage tracked down witness testimonies, teacher and administration corroborations, and student accounts from the past five years. Mage, Coppola, and Levenson were able to find several students, former and current, who had filed formal complaints against Bissell, yet had received no action from the district.

“There is an emotional, lived reality for that student that is separate from the bureaucratic process of filing a report,” Coppola said. “Sending it up the chain and having no conclusion handed down is not a satisfying response to a student. And being their teacher, I’m more aligned with that [perspective] than the institutional response.”

In uncovering several accounts of abuse that had all been reported to the district over the past several decades, Mage and Coppola could only wonder one thing: why had no one noticed this before?

“Part of what the system has going for it is that kids graduate,” Coppola said. “There’s high turnover by nature and the memory disappears.”

In addition to high administrator turnover, BHS has struggled to retain a Title IX coordinator for more than one year at a time. Mage and Coppola still don’t know where students’ harassment complaints currently are or whether they’re ever looked at again. According to Mage, there is “no institutional memory to corroborate any of this.” Thus, the worst punishment Bissell had received until now was a bad reputation passed down among friends and siblings.

“Going into high school, I knew the name Bissell,” said AC senior Emmy Sampson, one of the co-presidents of BHS Stop Harassing. She recalled that Levenson had long been aware of Bissell’s actions and frequently reported them to the administration. “I knew that he was very creepy and I knew that he targeted girls in his class. … He was a teacher to watch out for.”

Coppola pointed out that some teachers had been around long enough to become aware of Bissell’s behavior, yet the incriminating evidence had remained nothing more than “just a rumor.”

“When children say something, is it just a rumor?” Coppola said. “How many children need to say it before it’s no longer a rumor? We work in the system, but that doesn’t mean that we have to let the system hurt students like this.”

Levenson gave a shout out to the teachers that managed to do the right thing over and over again despite the lack of response from the administration. Additionally, the work of parents and volunteers like Levenson has provided both activism and emotional support for students at BHS for many years.

“They listened to their students,” Levenson said. “They brought them to their administrator and helped advocate for the student. For those teachers, it’s the same experience as it is for the students. … If you’re a teacher and you’re holding the fact that your institution is not protecting students, well that’s the core of who you are and an additional heartbreak.”

Coppola described the “click-through” harassment training teachers receive, which emphasized legal liability over emotional trauma, centering the teacher’s role as a court-mandated reporter rather than a supportive figure to students. However, according to Coppola, this training ignores the emotional needs of the students, as well as the dynamics to take into account. She called for specific harassment training on four different dynamics: staff to staff, staff to student, student to staff, and student to student.

Abby Lamoreaux, chief of women’s equity and student rights at BHS, explained student leadership’s plans for the coming school year. Lamoreaux said that they plan to work with the administration to create a safer sports and Physical Education environment.

Despite several deep rooted systemic issues at BHS, Phillips explained that they have changed for the better since her time as a student. She recalled receiving a personal phone call from former Principal Erin Schweng in early 2020 when Phillips initially filed the police report.

That phone call was “a step in the right direction,” said Phillips. When she was younger, “a gesture like that would’ve made a big difference. If there had been any kind of intervention or if I’d ever spoken to a counselor or anybody. But I got lost.”

Levenson, who has seen multiple of her children graduate from BHS, remarked that the administration has made some strides in terms of listening to students’ needs.

Sampson felt, however, that there was a lack of proper communication between the administration and students. She expressed a need for administrators to acknowledge the long-time pattern of Bissell’s harassment that went unnoticed and unpunished for years in BUSD.

“The dam burst in February of 2020 with a walkout,” Mage said. “It was desperation that they were crying out to be heard. I think that [2003] yearbook was their bathroom wall.”

In acknowledging that desperation, Mage described being inspired by the BHS students who had fought hard for change just before school got shut down. While Mage and Coppola said that they were working to build off of the momentum of student activists, Lamoreaux described student leadership wanting to start the next year with energy fueled from the lawsuit.

“Somebody has to tell these young women that what happened to them was wrong. They don’t have to go through this alone,” Levenson said. “And they’re going to be part of the process of creating a different world that we expect for every single [high schooler], middle schooler, and elementary school child in BUSD.”