From its very creation, when student activists took the park in defiance of Republican Governor Ronald Regan, the history of People’s Park has been inseparable from the counterculture era. Yet 40 years later, Berkeley’s resistance to authority and the University of California (UC) system is all that remains of the park's storied history. In 2018, UC Berkeley unveiled a plan to build student and supportive housing on the lot, while still leaving some of the park open. Recently, as the university moved ahead with the plan by taking soil samples, protestors have intensified their fight against the development. Despite actions of activists, building student and affordable housing is the best way to preserve the progessive legacy of People’s Park.

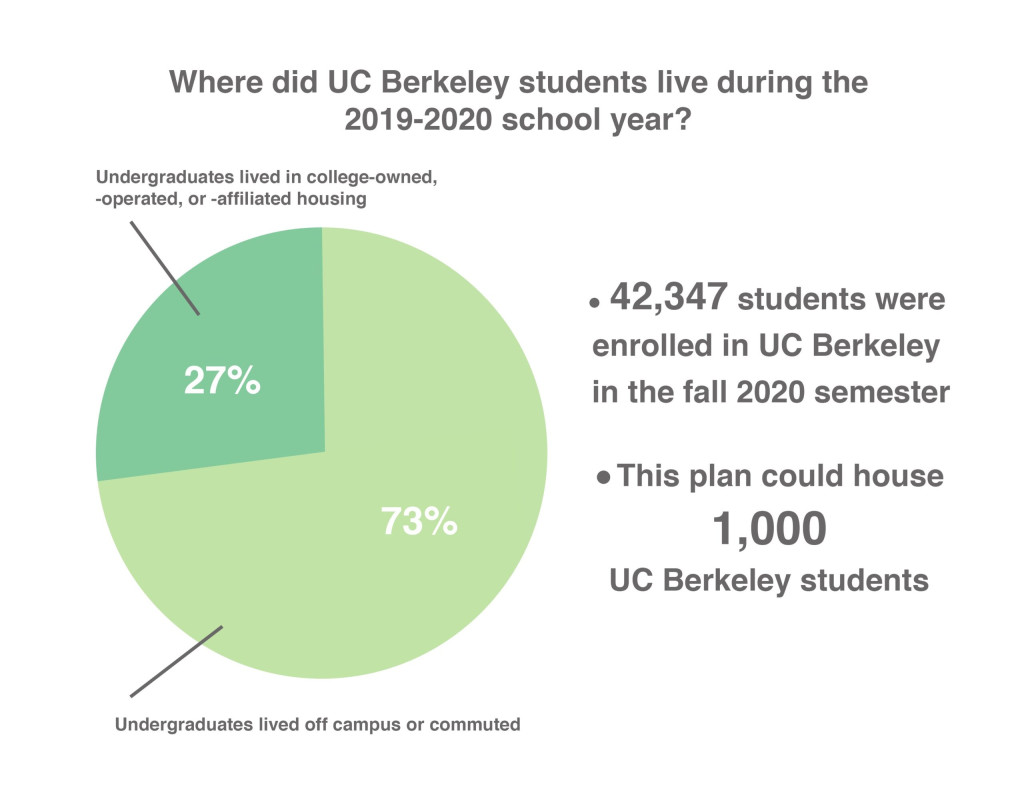

As the city goes through a housing crisis exacerbated by students pressed to find lodging, the need to build student housing is greater than ever. Building student housing doesn’t just help UC Berkeley students, it also takes the pressure off the rental market, driving prices to a more affordable range. The university’s plan also includes the development of between 75 and 125 units of supportive housing, which would not only provide housing for individuals experiencing homelessness, but case management and counseling for drug and alcohol use. Under this plan, the university could house and provide services to more than double the number of people currently residing in the park during the day. In other words, this plan would house a thousand students, provide much needed counseling and housing to all the people in the park, and still have spaces left for other homeless people.

It’s also impossible to talk about People’s Park without talking about crime. In a five year span, from January 2013 to January 2018, there were 125 assaults, 15 assaults with a deadly weapon and five rapes all reported in the park area. To put that in context, that is roughly 15 percent of the number of assaults that happened everywhere else in Berkeley during that time frame. The pervasiveness of crime in the area is because the lot was never meant to be a park. The surrounding buildings do not have a proper view of the area, allowing criminals to feel more comfortable perpetrating crime. The proposed housing units would be facing the remaining areas of the park, eliminating the area as a violent crime hotspot.

Despite misinformed or misguided attacks, there are three main valid concerns with the plan. The first is the displacement of unhoused inhabitants of People’s Park who choose to be unhoused, who don’t want to take advantage of the supportive housing. However, the park is neither a long-term residence — rules against sleeping overnight only stopped being enforced since the pandemic — nor a very safe residence. Even if it were a perfectly safe and long-term place to stay, the benefits of building would still far outweigh the costs. Although it hurts to displace such a vulnerable group, the less than 40 people who reside there could move to another green space, say Martin Luther King Jr. Civic Center Park, while hundreds and even thousands of other vulnerable groups, like renters struggling with soaring prices and houseless people who wish to be housed, will benefit.

The second main concern presented is the location of the plan on People’s Park given the many other undeveloped plots of land UC Berkeley owns. The fact of the matter is that People’s Park is just one of the many sites that UC Berkeley is undertaking to develop on as part of a plan to build seven thousand units for students to live in. While refusing to build higher buildings on Clark Kerr Campus or the Chancellor's mansion is undoubtedly wrong on the university’s part, that doesn’t mean that activists should throw a wrench in the university’s plan to house more of the students.

The third and most often repeated claim is that building housing would erase the park’s rich history. But the best way to commemorate that history is not to keep the space the same as it has been since the '60s. It’s time to embrace development of student and supportive housing in Berkeley.

The nostalgia for Berkeley’s long history of progressive politics is part of what makes this city great. But preserving People’s Park in its current state, while obstructing the development of housing that is desperately needed, is antithetical to that history. Boomers, it’s time to recognize that your time as a hippie didn’t stop the clock on issues facing society. The progressive politics of the '60s and '70s that wanted a park for the people now means demanding housing and care for at risk groups by taking strain off the housing market and housing the houseless.